African leaders have intensified calls for colonial-era crimes to be formally recognised, criminalised and addressed through meaningful reparations.

This renewed push took centre stage at a high-level conference held in Algiers, Algeria, where diplomats and senior officials gathered to advance an African Union resolution adopted earlier this year.

Algerian Foreign Minister Ahmed Attaf said his country’s painful experience under French rule underscored the need for compensation and the return of stolen property. He stressed that a strong legal framework would ensure restitution is treated as neither a gift nor a favour, but as a rightful obligation.

Attaf noted that Africa continues to pay a heavy price for colonial injustices, reflected today in systemic marginalisation and exclusion. He insisted the time had come for the continent to demand official recognition of the crimes committed during the colonial era, describing it as the first essential step toward true historical redress.

Although international statutes outlaw slavery, torture and apartheid, the United Nations Charter does not explicitly mention colonialism. That omission was a key focus of discussions during the African Union’s February summit, where leaders debated a unified position on reparations and the designation of colonisation as a crime against humanity.

Experts estimate that the economic cost of colonialism in Africa runs into the trillions. European powers extracted immense wealth—gold, diamonds, rubber and other minerals—while leaving African communities impoverished. In recent years, African states have also heightened demands for the return of cultural artefacts still housed in European museums.

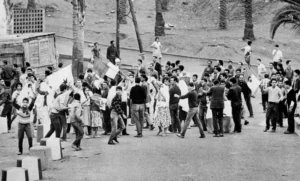

Attaf said Algeria’s selection as the host country was symbolic, given its history as one of the regions most deeply scarred by French colonial rule. Nearly a million European settlers enjoyed greater political and economic privileges, even though Algeria was legally part of France and its citizens were conscripted during the Second World War. The struggle for independence between 1954 and 1962 cost hundreds of thousands of lives, with widespread torture, forced disappearances and scorched-earth tactics used by colonial forces.

Also Read; Algeria’s Pivotal Conference: Call for Justice and Reparations

He added that Algeria’s historical experience continues to influence its stance on Western Sahara, which it views as Africa’s last colony. Despite growing support among some African Union member states for Morocco’s claim, Algeria maintains that the Sahrawi people are entitled to self-determination under international law.

For decades, Algeria has advocated the use of international legal mechanisms to address colonial legacies, even as its leaders carefully navigate sensitive diplomatic relations with France. Although French President Emmanuel Macron acknowledged in 2017 that aspects of France’s colonial history in Algeria amounted to crimes against humanity, Paris has yet to issue a formal apology or return significant cultural artefacts, such as the historic 16th-century cannon Baba Merzoug.

The debate over reparations is also gaining momentum in other parts of the world. Earlier in November, the media reported on a Caribbean delegation preparing to visit the UK to push for redress for slavery and colonial-era exploitation. Caribbean governments are calling for full recognition of the enduring impact of colonialism, formal apologies from former colonisers and substantive reparative measures.!