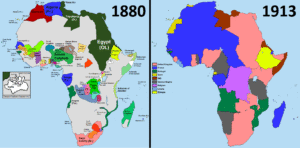

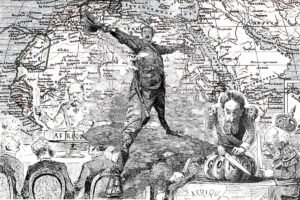

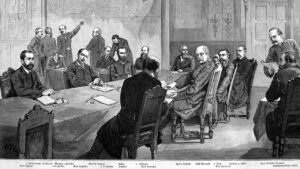

A century after European empires carved up the continent in the infamous Scramble for Africa, a new geopolitical contest is unfolding—this time global in scope, but once again rooted in Africa’s strategic minerals.

From the cobalt fields of the Democratic Republic of Congo to Tanzania’s emerging rare‐earth and graphite corridors, global powers are repositioning themselves in a race that African analysts warn mirrors the coercive tactics of an earlier era. The tools may have changed—diplomacy, security cooperation, financial leverage—but the strategic intent feels strikingly familiar.

In the DRC, cobalt, coltan, and rare earths have done little to uplift the communities that sit atop them. Instead, the wealth beneath the soil has turned provinces into theaters of war, where armed groups—some indirectly enabled by external interests—sustain cycles of violence that keep extraction cheap and accountability distant. A 2023 UN Group of Experts report observed that “mineral supply chains continue to provide revenue to both non‑state armed groups and individuals with connections to political and business actors.” As one Congolese civil society leader put it: “Our minerals are a blessing to everyone except the people who own the land.”

This pattern of strategic pressure is not confined to conflict zones. It is now emerging in countries once protected by stability and strong institutions. Tanzania, for example, is becoming a key player in graphite, nickel, helium, and rare earths—and as a result, is increasingly courted by global powers. Diplomatic missions are proliferating, investment pledges are escalating, and technical partnerships are expanding. But behind the rhetoric of “cooperation” lies a sharper competition for long-term access.

The late Kwame Nkrumah warned in 1965 that “neocolonialism is the worst form of imperialism because it gives the illusion of independence.” His words ring true as Western, Chinese, and Middle Eastern actors intensify their bid for mineral access. Africa is no longer just a resource frontier—it has become the center of a global struggle for industrial and political supremacy.

Also Read; Algiers Hosts Ministerial Conference on Local Medicine

Tanzania’s own history offers a cautionary reminder. In the 1970s, Julius Nyerere cautioned against foreign assistance that masks influence, saying, “We must guard against the subtle pressures which come in the guise of aid or friendship, for the purpose is influence, not partnership.” That warning resonates today as external players challenge policies that prioritize local content, value addition, and sovereign control.

Security cooperation adds another layer to the contest. The United States insists that AFRICOM exists solely for counterterrorism and maritime security. But critics, like Professor Horace Campbell, argue that its footprint overlaps conspicuously with mineral‑rich regions—a sign, they say, of “the militarization of U.S. policy on the continent under the cover of security while economic interests are pursued.” Washington denies any resource-driven motives, but the perception of entangled economic and military interests shapes politics from Dar es Salaam to Kinshasa.

Beyond the military ties, economic levers quietly steer the game. Credit rating agencies, donor institutions, and compliance bodies influence how capital flows into African markets. When African governments pursue diversified partnerships—especially with non‑Western players—warnings about “debt distress,” “autocratic drift,” or “opaque deals” often emerge. According to the African Union Peace and Security Council, such interference, even under the skirts of “support,” can erode sovereignty.

This influence system is rarely overt. It arrives through subtle mechanisms—loan conditions, technical assistance, NGO frameworks, investment arbitration rules, and diplomatic pressure cloaked in development language. As one East African diplomat put it: “When you comply, they call you a partner. When you negotiate, they call you a problem.” For many Africans, these dynamics are the lingering “germs” of imperialism that Frantz Fanon described, now hidden in governance benchmarks, security alignments, and disparaging narratives about African self-assertion.

Also Reads; Algiers Hosts Ministerial Conference on Local Medicine

Still, the continent is no longer passive.

Countries like Tanzania, Namibia, Zambia, Botswana, Rwanda, and South Africa are pushing back—strengthening mining legislation, renegotiating legacy contracts, and demanding local processing. At the same time, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) is offering a continental framework to reduce fragmented, bilateral dependencies. Civil society, youth movements, and think tanks are increasingly vocal, calling for Africa to become a price setter—not a price taker.

As Nyerere famously reminded the world: “Africa must not be satisfied with crumbs from a rich man’s table; we produce much of the world’s wealth, so we must control it.” His words could not be more pertinent today. The global shift to clean energy, digital infrastructure, and advanced manufacturing depends on African minerals. But without strong governance and a collective strategy, Africa risks repeating historical patterns of exploitation.

The new scramble for Africa is here—and so is a new Africa: more aware, more assertive, and far less willing to be managed. A century after the first scramble, the contest is no longer for Africa alone—it is a struggle for global power, and once again, Africa sits at the heart of it.